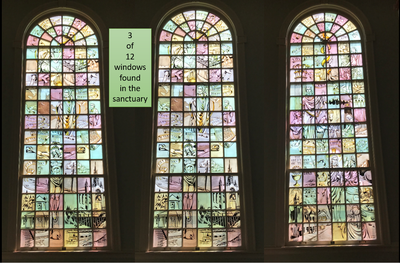

St. Paul's Lutheran Church has a rich history. The congregation has worshiped in four different buildings. The present church building was built in 1959. The sanctuary windows provide a Biblical story as well as a history of the congregation.

View a video of the history of St. Paul's. Click here.

A Little History. It all began in 1794...

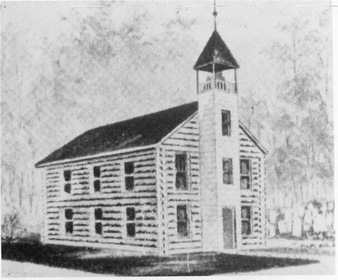

The first church building for St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, then called the German Evangelical Lutheran Congregation, was constructed late in 1794, just months after the congregation was organized and the lot was purchased in downtown Cumberland. This building faced Center Street, not directly on the corner with Baltimore Street, as the two subsequent churches were.

Cumberland was beginning to make the transition from frontier town to settlement, and this congregation attracted German, mostly farmers, many via earlier settlements in Pennsylvania, where churches there helped nurture this new congregation, a favor that would be returned later.

The first pastor, the Rev. Friedrich Wilhelm Lange, had started out serving a wide area in Pennsylvania and Western Maryland. Rev. Lange served the congregation until 1805.

Services were held whenever the pastor made it to town (his home was in Berlin, Pa., and he served churches as far away as Somerset), apparently every six to 10 weeks, based on the clusters of child baptisms recorded in the Kirchen Buch. It’s unlikely that there were catechism classes or funerals, but baptisms and marriages were performed at the end of the occasional service. There are no good estimates of the size of the congregation in those days.

The log church continued to serve the Lutheran congregation, and on occasion the Episcopalian and Presbyterian congregations until both had built their own buildings, the last around 1839. It was around this time that the Lutherans started to recognize the need for a new building, as the log church was suffering from age and neglect.

Nonetheless, the new building took many years to build, until the unsafe nature of the old building forced their hand. But that did not prevent them from turning the log church into a parsonage, where it was renovated to house the pastors and their family for a number of years until the pastors finally refused to live in it because of the state of disrepair. The building was finally taken down in the 1850s.

Fun fact: For the 175th anniversary in 1979, someone created a scale model of the log church, which sat in the corner of St. Paul’s parking lot next to Smallwood Street for a period of time. (Does anyone know who built it and what happened to it?)

*Source: From Generation to Generation - St. Paul's Lutheran Church - 1794-1994

Cumberland was beginning to make the transition from frontier town to settlement, and this congregation attracted German, mostly farmers, many via earlier settlements in Pennsylvania, where churches there helped nurture this new congregation, a favor that would be returned later.

The first pastor, the Rev. Friedrich Wilhelm Lange, had started out serving a wide area in Pennsylvania and Western Maryland. Rev. Lange served the congregation until 1805.

Services were held whenever the pastor made it to town (his home was in Berlin, Pa., and he served churches as far away as Somerset), apparently every six to 10 weeks, based on the clusters of child baptisms recorded in the Kirchen Buch. It’s unlikely that there were catechism classes or funerals, but baptisms and marriages were performed at the end of the occasional service. There are no good estimates of the size of the congregation in those days.

The log church continued to serve the Lutheran congregation, and on occasion the Episcopalian and Presbyterian congregations until both had built their own buildings, the last around 1839. It was around this time that the Lutherans started to recognize the need for a new building, as the log church was suffering from age and neglect.

Nonetheless, the new building took many years to build, until the unsafe nature of the old building forced their hand. But that did not prevent them from turning the log church into a parsonage, where it was renovated to house the pastors and their family for a number of years until the pastors finally refused to live in it because of the state of disrepair. The building was finally taken down in the 1850s.

Fun fact: For the 175th anniversary in 1979, someone created a scale model of the log church, which sat in the corner of St. Paul’s parking lot next to Smallwood Street for a period of time. (Does anyone know who built it and what happened to it?)

*Source: From Generation to Generation - St. Paul's Lutheran Church - 1794-1994

225 Tidbits - Whose Language is it Anyway?

Most, if not all, Lutherans in the days of St. Paul’s founding were German immigrants. While they were slowly learning English for commerce and other interactions, when they were at Christ’s Church (St. Paul’s original name), the German language ruled the day. Preaching, scripture readings and record-keeping were all in German at first. It was more than a decade into the life of the congregation before English began to creep in, during the ministry of Rev. John George Boettler – or Butler, the first pastor to preach in English … just not all the time.

The next pastor, Rev. J.F.C. Heyer, who came in 1818, and especially his wife, Mary, recognized that English was going to be the dominant language in their community, and if they were to serve the community – and keep the congregation’s young people – services should be in English. Rev. Heyer, however, did not speak English well, but he struggled along with his wife’s encouragement and tutoring.

While English had taken hold within the congregation, another wave of immigration from Europe began in the 1830s, many from Germany. Wanting to hear the Gospel in their native tongue, the asked the pastor at the time, Rev. John Kehler, to preach to them in German. He agreed, forming a German Lutheran congregation that would share the same roof and pastor with the English one. By 1841, the German Lutheran congregation had organized its own vestry, which met jointly with the English vestry. However, as the German congregation grew and wanted more designated time for services, conflicts grew as well.

Things finally came to a head when the English congregation wanted to call a pastor who spoke German poorly, then the Germans suggested a pastor who could not speak English well. Ultimately, each congregation called its own pastor, and the groups co-existed under the same roof for a little while longer.

Ultimately, however, the English congregation felt the pressure of four other English-speaking Christian churches, and decided that the German congregation could stand on its own, “disinviting” that congregation, giving them about a year to build a church and vacate.

The church they dedicated in 1849 was the Town Clock Church,* which still stands on Bedford Street. That the congregation continued to grow, building a church on the corner of Bedford and Columbia streets (which later became Beth Jacob Synagogue), and finally ending up in a modern building on Frederick Street. We call it St. Luke’s Lutheran Church, one of our sister congregations.

Cumberland trivia: When the first St. Luke’s was being built, Sts. Peter and Paul’s Catholic Church was also under construction. The city of Cumberland offered a clock to the church that was completed first. St. Luke’s won. Next time you are in the St. Paul’s parking lot, look up at Sts. Peter and Paul’s steeple. You’ll see a blank space where their clock would have gone.

*Source: From Generation to Generation: Two Hundred Years in the Life of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church

The next pastor, Rev. J.F.C. Heyer, who came in 1818, and especially his wife, Mary, recognized that English was going to be the dominant language in their community, and if they were to serve the community – and keep the congregation’s young people – services should be in English. Rev. Heyer, however, did not speak English well, but he struggled along with his wife’s encouragement and tutoring.

While English had taken hold within the congregation, another wave of immigration from Europe began in the 1830s, many from Germany. Wanting to hear the Gospel in their native tongue, the asked the pastor at the time, Rev. John Kehler, to preach to them in German. He agreed, forming a German Lutheran congregation that would share the same roof and pastor with the English one. By 1841, the German Lutheran congregation had organized its own vestry, which met jointly with the English vestry. However, as the German congregation grew and wanted more designated time for services, conflicts grew as well.

Things finally came to a head when the English congregation wanted to call a pastor who spoke German poorly, then the Germans suggested a pastor who could not speak English well. Ultimately, each congregation called its own pastor, and the groups co-existed under the same roof for a little while longer.

Ultimately, however, the English congregation felt the pressure of four other English-speaking Christian churches, and decided that the German congregation could stand on its own, “disinviting” that congregation, giving them about a year to build a church and vacate.

The church they dedicated in 1849 was the Town Clock Church,* which still stands on Bedford Street. That the congregation continued to grow, building a church on the corner of Bedford and Columbia streets (which later became Beth Jacob Synagogue), and finally ending up in a modern building on Frederick Street. We call it St. Luke’s Lutheran Church, one of our sister congregations.

Cumberland trivia: When the first St. Luke’s was being built, Sts. Peter and Paul’s Catholic Church was also under construction. The city of Cumberland offered a clock to the church that was completed first. St. Luke’s won. Next time you are in the St. Paul’s parking lot, look up at Sts. Peter and Paul’s steeple. You’ll see a blank space where their clock would have gone.

*Source: From Generation to Generation: Two Hundred Years in the Life of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church

225 Tidbits - The Second Church: Built in Pieces

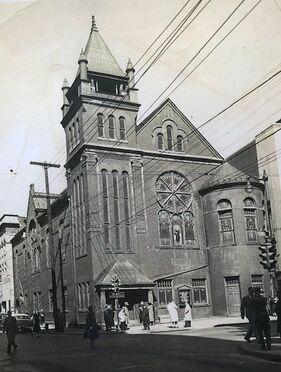

By the 1830s, the log church that had been Christ (St. Paul’s) Lutheran Church’s home since 1794 had become dilapidated, and congregations from other denominations that had been “incubated” in the old church had left and built churches of their own. By 1836, the Vestry had begun discussions about building a new church home, but an effort to raise funds from the congregation failed, then the banks failed a year later. Banks and businesses closed, so the plan was delayed. Nevertheless, time and decay marched on. While the Vestry considered whether to renovate or replace the old church, it was deemed to be in “run-down condition, unfit and unsafe for worship.” The decision was made to build anew, and the space next to the log church, which faced Centre Street, was designated for the new church, oriented to front on Baltimore Street. The congregation agreed that the new church would be 70 feet long and as wide as the lot would allow, with a 20-foot setback from Baltimore Street. (Incidentally, one vestryman felt a larger building was necessary, and since he could not sway the Vestry, he simply arrived at the site overnight and moved the stakes designating the building’s dimensions forward by 10 feet. The building was under way when the deception was discovered.)

This church building was a work in progress for better than a decade. Much of the work was donated by members of the congregation. The cornerstone was laid in 1842, (the same cornerstone found in the front of the current St. Paul’s near the Smallwood Street door). By 1843, a single room to hold services had been achieved. In 1844, a basement lecture hall was added, along with pews and a pulpit in the sanctuary. In 1845, another basement room was created for the Sunday school primary department. The exterior was simply a plain front until the Vestry adopted a resolution saying that, “in view of the unfinished and unsightly appearance of the Church Front,” a new one “shall be completed in a style demanded by the growing importance of the town and the central position occupied by the church.” A new women’s group, the Ladies Organization, raised the funds for the new church front, but not trusting the Vestry to act, they held back the money until a definite plan was in place. That didn’t happen until 1848, and the work was completed in 1854. The steeple was another sticking point, as a halffinished structure topped the building until 1859, when a more-imposing steeple costing $450 was installed. Gas lighting was installed in 1860. The final church was a two-story brick building, with a narrow yard between the church and the street enclosed by an iron fence. The first story, housing two gathering rooms (one called St. Paul’s, the first use of that name by this congregation) and a kitchen, was partially below ground, entered by stairs from Centre Street. The main entrance was from Baltimore Street. The front of the church held a vestibule that covered the width of the building, with doors leading to the “auditorium” at either side. The chancel was formed by an altar rail setting off a 12-by-20-foot space. The Pulpit stood on a platform in the center of the rear of the chancel. A table in front of the pulpit served as the altar.

*Source: From Generation to Generation: Two Hundred Years in the Life of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church

By the 1830s, the log church that had been Christ (St. Paul’s) Lutheran Church’s home since 1794 had become dilapidated, and congregations from other denominations that had been “incubated” in the old church had left and built churches of their own. By 1836, the Vestry had begun discussions about building a new church home, but an effort to raise funds from the congregation failed, then the banks failed a year later. Banks and businesses closed, so the plan was delayed. Nevertheless, time and decay marched on. While the Vestry considered whether to renovate or replace the old church, it was deemed to be in “run-down condition, unfit and unsafe for worship.” The decision was made to build anew, and the space next to the log church, which faced Centre Street, was designated for the new church, oriented to front on Baltimore Street. The congregation agreed that the new church would be 70 feet long and as wide as the lot would allow, with a 20-foot setback from Baltimore Street. (Incidentally, one vestryman felt a larger building was necessary, and since he could not sway the Vestry, he simply arrived at the site overnight and moved the stakes designating the building’s dimensions forward by 10 feet. The building was under way when the deception was discovered.)

This church building was a work in progress for better than a decade. Much of the work was donated by members of the congregation. The cornerstone was laid in 1842, (the same cornerstone found in the front of the current St. Paul’s near the Smallwood Street door). By 1843, a single room to hold services had been achieved. In 1844, a basement lecture hall was added, along with pews and a pulpit in the sanctuary. In 1845, another basement room was created for the Sunday school primary department. The exterior was simply a plain front until the Vestry adopted a resolution saying that, “in view of the unfinished and unsightly appearance of the Church Front,” a new one “shall be completed in a style demanded by the growing importance of the town and the central position occupied by the church.” A new women’s group, the Ladies Organization, raised the funds for the new church front, but not trusting the Vestry to act, they held back the money until a definite plan was in place. That didn’t happen until 1848, and the work was completed in 1854. The steeple was another sticking point, as a halffinished structure topped the building until 1859, when a more-imposing steeple costing $450 was installed. Gas lighting was installed in 1860. The final church was a two-story brick building, with a narrow yard between the church and the street enclosed by an iron fence. The first story, housing two gathering rooms (one called St. Paul’s, the first use of that name by this congregation) and a kitchen, was partially below ground, entered by stairs from Centre Street. The main entrance was from Baltimore Street. The front of the church held a vestibule that covered the width of the building, with doors leading to the “auditorium” at either side. The chancel was formed by an altar rail setting off a 12-by-20-foot space. The Pulpit stood on a platform in the center of the rear of the chancel. A table in front of the pulpit served as the altar.

*Source: From Generation to Generation: Two Hundred Years in the Life of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church

225th Tidbits – The Church Struggles to Finance Itself

The second half of the 19th century for Christ’s Lutheran Church was definitely a challenge financially – many of its issues self-inflicted, and some of its solutions a little puzzling.

In 1842, when the second church began construction, the church housed two congregations – one German and one English, and it also supported two rural churches, one at Murley’s Branch near Flintstone and Union Church on the Bedford Road. Those four congregations’ support maintained the church building, which included new debt for construction, as well as the salary and parsonage for the pastor.

With the departure of the German congregation a few years later, the English congregation was left with the full debt for the new building and the pastor’s support. The two “country churches” were left to wither. Debt grew, as the church often borrowed to pay creditors.

The members of the congregation were generally not wealthy, nor was there much of a tradition of financially supporting a church among them. Instead, a variety of schemes were attempted:

The second half of the 19th century for Christ’s Lutheran Church was definitely a challenge financially – many of its issues self-inflicted, and some of its solutions a little puzzling.

In 1842, when the second church began construction, the church housed two congregations – one German and one English, and it also supported two rural churches, one at Murley’s Branch near Flintstone and Union Church on the Bedford Road. Those four congregations’ support maintained the church building, which included new debt for construction, as well as the salary and parsonage for the pastor.

With the departure of the German congregation a few years later, the English congregation was left with the full debt for the new building and the pastor’s support. The two “country churches” were left to wither. Debt grew, as the church often borrowed to pay creditors.

The members of the congregation were generally not wealthy, nor was there much of a tradition of financially supporting a church among them. Instead, a variety of schemes were attempted:

- Subscriptions, in which vestry members, at the beginning of each “pastor’s year” (pastors were engaged by the year), called upon members of the congregation to pledge a certain sum of money to be given to the church “at some

- Pewletting, in which pews were rented to members of the congregation. The choicest pews went for $20. Others were $15 and $5, but about half the pews remained free. One member, Gustavus Beall, condemned the practice early on as “un-christian-like and discriminatory,” saying, “the best seats in God’s sanctuary should not be occupied by those who were best able to pay for them.” The practice continued for another decade, but it was abolished by 1871.

- Charging for lectures or selling homemade articles during pre-Christmas “fairs,” one of the more lucrative practices.

- Due-bills, which served as a letter of credit, assuming a merchant would be willing to accept it. The church relied greatly on merchant Jonathan Butler, who was the son of the Rev. John George Butler, as well as an elder of the congregation. He generally carried about $400 in debt for the church in his account each year.

- Selling property, carving off pieces of the original one-acre lot, in 10 separate transactions, starting in 1844. By the time the third church was built, the only piece left was that on which the building sat.

- And then there’s the church’s foray into the real estate rental business, which will have to wait for another edition of “225th Tidbits.”

225 Tidbits – Building the Third Church

The second Christ’s Church, started in 1842 and completed over a series of years, had no longer a life span

than the first church made of logs. In particular, the basement story, where a lecture hall and room for the

primary department of the Sunday school, had become so damp that it was of little use.

Pastor McAtee, who served from 1879-1883, was not interested in renovating the 1842 building and the

congregation went along with his wishes, so no changes or plans for changes were made. It became

apparent, however, that the congregation wanted something to happen – renovate or rebuild – but it took

them a very long time settle on a plan.

Ultimately, the congregation was presented with two choices: renovate the current building, or sell the

current property and rebuild elsewhere in Cumberland. Funds were being raised by 1888, but no plan could

be settled on. Interestingly, the choice of tearing down the current church and building on the same site –

what eventually happened – was not presented to the congregation.

The congregation and Vestry went back and forth over the course of several years, first deciding on

renovation, then rejecting the plans developed to stay within the set budget. Sometime later, plans were

submitted that would involve tearing down the current building and rebuilding on the site, but they were

rejected over disagreements on cost and design. The discussions continued, with one plan substituting for

less expensive materials – pine instead of oak, no cut stone, etc. Those plans weren’t adopted, either.

After more back-and-forth, the congregation was finally presented with three options – sell and build

elsewhere, build on the present site, or remodel. The suggestion to build elsewhere was soundly

defeated, 114 to 34. The choice of building at the current site (in a vote held the following week) was

adopted 141 to 33. This was five years after the discussions and fundraising had begun.

And it still wasn’t time. The Vestry apparently got cold feet contemplating taking on the debt of a new building, and decided – without the congregation’s approval – to defer the project again.

Rev. John W. Finkbinder, the pastor who had shepherded the project almost since his first arriving in Cumberland, didn’t let the matter die, and finally an architect and builder were secured and work began.

Sunday, July 1, 1894, was the last service to be held in the second church. The congregation held services at B’er Chayim Temple, the synagogue at the corner of Union and South Centre streets, during the 14 months of construction.

Pastor Finkbinder, sadly, was not able to preside over the services in the new church. In the fall of 1894, he announced that his wife’s failing health required that they move to a better climate.

The new church was dedicated Sept. 22, 1895, with the new name of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church.

Source: From Generation to Generation: Two Hundred Years in the Life of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church.

The second Christ’s Church, started in 1842 and completed over a series of years, had no longer a life span

than the first church made of logs. In particular, the basement story, where a lecture hall and room for the

primary department of the Sunday school, had become so damp that it was of little use.

Pastor McAtee, who served from 1879-1883, was not interested in renovating the 1842 building and the

congregation went along with his wishes, so no changes or plans for changes were made. It became

apparent, however, that the congregation wanted something to happen – renovate or rebuild – but it took

them a very long time settle on a plan.

Ultimately, the congregation was presented with two choices: renovate the current building, or sell the

current property and rebuild elsewhere in Cumberland. Funds were being raised by 1888, but no plan could

be settled on. Interestingly, the choice of tearing down the current church and building on the same site –

what eventually happened – was not presented to the congregation.

The congregation and Vestry went back and forth over the course of several years, first deciding on

renovation, then rejecting the plans developed to stay within the set budget. Sometime later, plans were

submitted that would involve tearing down the current building and rebuilding on the site, but they were

rejected over disagreements on cost and design. The discussions continued, with one plan substituting for

less expensive materials – pine instead of oak, no cut stone, etc. Those plans weren’t adopted, either.

After more back-and-forth, the congregation was finally presented with three options – sell and build

elsewhere, build on the present site, or remodel. The suggestion to build elsewhere was soundly

defeated, 114 to 34. The choice of building at the current site (in a vote held the following week) was

adopted 141 to 33. This was five years after the discussions and fundraising had begun.

And it still wasn’t time. The Vestry apparently got cold feet contemplating taking on the debt of a new building, and decided – without the congregation’s approval – to defer the project again.

Rev. John W. Finkbinder, the pastor who had shepherded the project almost since his first arriving in Cumberland, didn’t let the matter die, and finally an architect and builder were secured and work began.

Sunday, July 1, 1894, was the last service to be held in the second church. The congregation held services at B’er Chayim Temple, the synagogue at the corner of Union and South Centre streets, during the 14 months of construction.

Pastor Finkbinder, sadly, was not able to preside over the services in the new church. In the fall of 1894, he announced that his wife’s failing health required that they move to a better climate.

The new church was dedicated Sept. 22, 1895, with the new name of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church.

Source: From Generation to Generation: Two Hundred Years in the Life of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church.

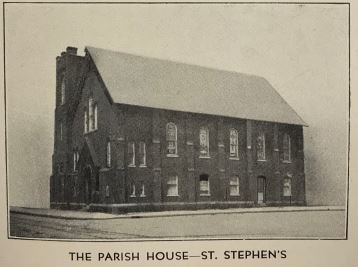

225 Tidbits: The St. Stephen’s Chapter

Following the building of the third church and at the beginning of the new century, differences arose for reasons that are not entirely clear, but whose impact was shocking and dramatic.

Parishioners were refusing to donate to help the congregation pay off the construction debt, and families were leaving for other churches in the city. The issue came to a head at a Vestry meeting in early 1902.

The meeting began routinely. Then a resolution was read and unanimously adopted that indicated that “a large portion of the members” of St. Paul’s were not in accord with the Rev. T.J. Yost. The resolution requested that Pastor Yost resign. The Vestry had hoped to end the matter quietly, but Yost refused, determined to “fight it out.”

A petition signed by 221 parishioners called for a congregational meeting, held several weeks later. Yost, his friends and some confused members who thought the meeting was over walked out. When order was restored (and some of the wandering parishioners returned), the gathered congregants unanimously ratified the request for Yost’s resignation. He agreed to resign the following week.

Trying to smooth things over, the Vestry paid him a severance of two month’s wages. The discord had apparently made it into the local newspapers, since they felt the need to refute charges of “locking the doors against the pastor.” Yost also said he regretted the trouble and closed the meeting with a prayer. The Vestry thought the problems were solved. They were wrong. Two weeks later, Rev. Yost and 86 members met in a church just a block down Centre Street, on the corner of Union Street, opposite the B’er Chayim Temple. They declared themselves “The First English Lutheran Church of Cumberland, Md.,” soon after renaming the congregation St. Stephen’s Lutheran Church.

The Maryland Synod objected, and their application to join the synod where they were located was denied. Instead, St. Stephen’s applied to join the Allegany Synod of Pennsylvania, and were accepted.

Pastor Yost was never listed as a pastor of St. Stephen’s, that position instead going to the Rev. Dr. M.L. Young, who led the congregation in purchasing the church building in which they had first met.

For the next 25 years, St. Paul’s and St. Stephen’s congregations operated just a block away from one another. The Rev. Hixon T. Bowersox became pastor of St. Paul’s in 1927. He quickly became aware that St. Stephen’s congregation was struggling when its members began to ask if they could join St. Paul’s. Rather than allowing St. Stephen’s to dwindle further, he invited the Council of St. Stephens to talk about a merger. He found them agreeable, and the churches soon reunited. The Vestry contained members of both groups, and the properties (and debts) were merged. The St. Stephen’s church building became the Parish Hall for St. Paul’s (serving in that capacity until 1946, when it was sold in the first step of moving the congregation to Washington Street.)

“Today it can be said without fear of contradiction that so complete is the unity that no one realizes that they were ever members of any other congregation than St. Paul’s,” Dr. Bowersox wrote in 1944.

Following the building of the third church and at the beginning of the new century, differences arose for reasons that are not entirely clear, but whose impact was shocking and dramatic.

Parishioners were refusing to donate to help the congregation pay off the construction debt, and families were leaving for other churches in the city. The issue came to a head at a Vestry meeting in early 1902.

The meeting began routinely. Then a resolution was read and unanimously adopted that indicated that “a large portion of the members” of St. Paul’s were not in accord with the Rev. T.J. Yost. The resolution requested that Pastor Yost resign. The Vestry had hoped to end the matter quietly, but Yost refused, determined to “fight it out.”

A petition signed by 221 parishioners called for a congregational meeting, held several weeks later. Yost, his friends and some confused members who thought the meeting was over walked out. When order was restored (and some of the wandering parishioners returned), the gathered congregants unanimously ratified the request for Yost’s resignation. He agreed to resign the following week.

Trying to smooth things over, the Vestry paid him a severance of two month’s wages. The discord had apparently made it into the local newspapers, since they felt the need to refute charges of “locking the doors against the pastor.” Yost also said he regretted the trouble and closed the meeting with a prayer. The Vestry thought the problems were solved. They were wrong. Two weeks later, Rev. Yost and 86 members met in a church just a block down Centre Street, on the corner of Union Street, opposite the B’er Chayim Temple. They declared themselves “The First English Lutheran Church of Cumberland, Md.,” soon after renaming the congregation St. Stephen’s Lutheran Church.

The Maryland Synod objected, and their application to join the synod where they were located was denied. Instead, St. Stephen’s applied to join the Allegany Synod of Pennsylvania, and were accepted.

Pastor Yost was never listed as a pastor of St. Stephen’s, that position instead going to the Rev. Dr. M.L. Young, who led the congregation in purchasing the church building in which they had first met.

For the next 25 years, St. Paul’s and St. Stephen’s congregations operated just a block away from one another. The Rev. Hixon T. Bowersox became pastor of St. Paul’s in 1927. He quickly became aware that St. Stephen’s congregation was struggling when its members began to ask if they could join St. Paul’s. Rather than allowing St. Stephen’s to dwindle further, he invited the Council of St. Stephens to talk about a merger. He found them agreeable, and the churches soon reunited. The Vestry contained members of both groups, and the properties (and debts) were merged. The St. Stephen’s church building became the Parish Hall for St. Paul’s (serving in that capacity until 1946, when it was sold in the first step of moving the congregation to Washington Street.)

“Today it can be said without fear of contradiction that so complete is the unity that no one realizes that they were ever members of any other congregation than St. Paul’s,” Dr. Bowersox wrote in 1944.

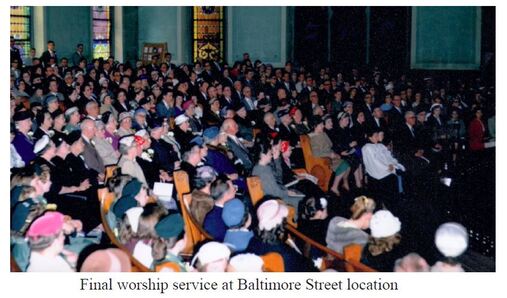

In advance of the 50th anniversary of the Washington Street church, a group of members who had belonged in the Baltimore Street era were asked to talk about their recollections of that period. Here are some of their memories (with some other recollections thrown in):

Dr. Hixon T. Bowersox ruled with an iron hand, according to Gerald Arthur. Catechism was always Friday night, regardless of the protests of the students, who would miss the local football games. The lessons never let out a minute before 8 p.m.

Mim says Christmas services were at 6 a.m. Christmas morning. Dr. Bowersox said there were too many drunks downtown on Christmas Eve.

Dr. Bowersox was also very outspoken (a feature that is evident in the History of St. Paul’s that he wrote). Alpha Reynolds’ father-in-law ran a tobacco store and newsstand downtown, which was open on Sunday mornings. Alpha said that Dr. Bowersox asked him where he was sending his children for Sunday school. He said a Methodist church in south Cumberland. Dr. Bowersox told him they needed to come to St. Paul's.

The children’s Sunday School was in the in the rounded portion to the right of the Baltimore Street entrance. Joy Douglas remembered watching mice running across the floor during Sunday school. Sabra recalled it being very crowded. The altar being used in the current sanctuary is believed to be the altar from the main Sunday School room.

Mim Sanner recalled that her family always sat under a window that was dedicated by Ernst & Sophia Barth. She always wondered who they were. Mrs. George Steiner sat in front of the Douglases every Sunday. She later said when her family moved to the new church, they sat in the same general area in the new sanctuary.

Congregational meetings often included a speaker and entertainment. There was plenty of discussion, but those in attendance differed over how open the conversations were.

Women always wore hats to church, but no one seemed to recall when the fashion changed, but it was after the move to the new church. (Mim Sanner remembered panicking one day because she left the house without a hat.)

A 1955 special program noted that the choir had 12 sopranos, 8 altos, 7 basses and 5 tenors.

*Source: From Generation to Generation - St. Paul's Lutheran Church - 1794-1994

225 Tidbits - Moving From "The Corner"

After 164 years on the corner of Baltimore and Centre Streets, St. Paul’s moved up the hill to the corner of Washington and Smallwood Streets. Yet neither that decision, nor the move, was at all simple. St. Paul’s was built on one of the original plots of what would become downtown Cumberland when it was first being laid out. The Cumberland that grew up with it transformed from a frontier town to a Civil War crossroads to a booming transportation hub serving the railroad, canal and National Road to an industrial city, Maryland’s second-largest.

With each building transition, there had been talk of changing locations. However, “To some, the corner was almost sacred; nothing but the forest and St. Paul’s had ever stood on that spot.” (Generation to Generation: St. Paul’s Lutheran Church 1794-1994)

The congregation had, over the years, sold off the large original property piece by piece, and with the sale of the old St. Stephens, used as a parish hall, in 1947, it was apparent that there was nowhere to grow in the current location.

At a congregational meeting on Oct. 3, 1949, following a long discussion, the congregation agreed to bid to purchase the Roman property on Washington Street, a mansion and extensive grounds built in 1897 by attorney J.P. Roman. That decision solidified the decision to move. The purchase was completed in December. The purchase was funded largely by the sale of the St. Stephen’s property.

It was at this point that serious planning and fund-raising began for the new building, which would not be built or occupied for nearly 10 years. To raise money, the church took up special collections, but all plans were put on hold during the Korean War, when materials for church buildings were being rationed. After it ended, St. Paul’s contracted with an organization that specialized in raising money for church construction. Dr. Bowersox delivered an impassioned sermon that urged the congregation – including those still clinging to “the corner” – to come together as a united force toward that goal. That campaign ultimately raised $214,000 in three-year pledges, more than its $200,000 goal. After the three-year period, this would be enough to build the first phase of the new church, the education building that would become Fellowship Hall.

Sadly, Dr. Bowersox’s declining health convinced him that he would not be the one to lead the congregation to its new home. “He expressed a desire to to be as David of old, who dreamed of the great temple of Jerusalem but was privileged only to make plans and gather materials. The work and glory of building it was left to his successor, Solomon.”

*Source: From Generation to Generation - St. Paul's Lutheran Church - 1794-1994

After 164 years on the corner of Baltimore and Centre Streets, St. Paul’s moved up the hill to the corner of Washington and Smallwood Streets. Yet neither that decision, nor the move, was at all simple. St. Paul’s was built on one of the original plots of what would become downtown Cumberland when it was first being laid out. The Cumberland that grew up with it transformed from a frontier town to a Civil War crossroads to a booming transportation hub serving the railroad, canal and National Road to an industrial city, Maryland’s second-largest.

With each building transition, there had been talk of changing locations. However, “To some, the corner was almost sacred; nothing but the forest and St. Paul’s had ever stood on that spot.” (Generation to Generation: St. Paul’s Lutheran Church 1794-1994)

The congregation had, over the years, sold off the large original property piece by piece, and with the sale of the old St. Stephens, used as a parish hall, in 1947, it was apparent that there was nowhere to grow in the current location.

At a congregational meeting on Oct. 3, 1949, following a long discussion, the congregation agreed to bid to purchase the Roman property on Washington Street, a mansion and extensive grounds built in 1897 by attorney J.P. Roman. That decision solidified the decision to move. The purchase was completed in December. The purchase was funded largely by the sale of the St. Stephen’s property.

It was at this point that serious planning and fund-raising began for the new building, which would not be built or occupied for nearly 10 years. To raise money, the church took up special collections, but all plans were put on hold during the Korean War, when materials for church buildings were being rationed. After it ended, St. Paul’s contracted with an organization that specialized in raising money for church construction. Dr. Bowersox delivered an impassioned sermon that urged the congregation – including those still clinging to “the corner” – to come together as a united force toward that goal. That campaign ultimately raised $214,000 in three-year pledges, more than its $200,000 goal. After the three-year period, this would be enough to build the first phase of the new church, the education building that would become Fellowship Hall.

Sadly, Dr. Bowersox’s declining health convinced him that he would not be the one to lead the congregation to its new home. “He expressed a desire to to be as David of old, who dreamed of the great temple of Jerusalem but was privileged only to make plans and gather materials. The work and glory of building it was left to his successor, Solomon.”

*Source: From Generation to Generation - St. Paul's Lutheran Church - 1794-1994

225th Tidbits – Building the “New” Church

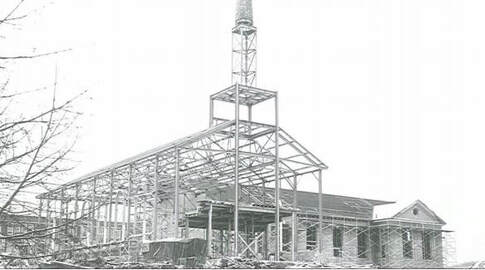

(Excerpts of “Reminiscences on the Construction of St. Paul’s,” presented by Bruce Douglas, a member of the building committee, on the occasion of the mortgage retirement nine years after the Washington Street church was completed) “… The plaster ornamentation around the ceiling of the sanctuary is typical of the classical roots of this (Georgian Colonial) architecture. One of the toughest problems in building this church was finding the craftsmen to do this highly skilled and specialized type of work. The plastering subcontractor could easily find men skilled in the flat work, but when it came to the intricate ornaments and moldings, he had to do them himself. Each one of the hundreds of dentils, so-called because of their resemblance to teeth, had to be cast by hand in hand-made molds. These were made on the job site. … All of the starburst ornaments, and others, were similarly hand-molded and cemented into place by one man and a helper. The numerous plaster moldings that you see were also hand-cast and reinforced in the old style with horsehair. “I also remember the ticklish job of erecting the seven and a half-ton pillars at the main entrance. Special slings were needed for the job, since steel cable would cut and mar the stone, which had been carefully turned and polished on enormous lathes. A collective sigh of relief punctuated the completion of this delicate but ponderous task. “Many of us will remember the erection of the steel frame for the steeple, and postponement, because of the risk created by high winds. Because of the height involved and the weight of the steel, it was one of the more spectacular rigging jobs the Cumberland has seen, and a large crowd was on hand for the show. Unhappily remembered also, was the severe injury suffered by one of our congregation, Randel Rowley, who was foreman of masonry construction. He was blown from a high scaffold by the gusty winds, and hospitalized for 80 days, legs in cast for 1 ½ years. “The problems in building this church started with the foundations. It was found that most of our footings were on good, solid limestone, except the northeast corner of the Fellowship Hall, which was on soft clay. It became necessary to drive steel piling to provide the needed bearing, and in some areas, 50-foot pilings were required. … “A need to economize on construction became evident when bids on the structure exceeded both the architect’s estimate and the church building budget. One of the first economy moves was to raise the elevation of all floors … by four feet, thereby saving a large volume of excavation and reducing the height of the retaining wall behind Fellowship Hall. A secondary benefit of this change was the elimination of steps down to the rear entrance, thus providing better access from the parking lot. …”

(Excerpts of “Reminiscences on the Construction of St. Paul’s,” presented by Bruce Douglas, a member of the building committee, on the occasion of the mortgage retirement nine years after the Washington Street church was completed) “… The plaster ornamentation around the ceiling of the sanctuary is typical of the classical roots of this (Georgian Colonial) architecture. One of the toughest problems in building this church was finding the craftsmen to do this highly skilled and specialized type of work. The plastering subcontractor could easily find men skilled in the flat work, but when it came to the intricate ornaments and moldings, he had to do them himself. Each one of the hundreds of dentils, so-called because of their resemblance to teeth, had to be cast by hand in hand-made molds. These were made on the job site. … All of the starburst ornaments, and others, were similarly hand-molded and cemented into place by one man and a helper. The numerous plaster moldings that you see were also hand-cast and reinforced in the old style with horsehair. “I also remember the ticklish job of erecting the seven and a half-ton pillars at the main entrance. Special slings were needed for the job, since steel cable would cut and mar the stone, which had been carefully turned and polished on enormous lathes. A collective sigh of relief punctuated the completion of this delicate but ponderous task. “Many of us will remember the erection of the steel frame for the steeple, and postponement, because of the risk created by high winds. Because of the height involved and the weight of the steel, it was one of the more spectacular rigging jobs the Cumberland has seen, and a large crowd was on hand for the show. Unhappily remembered also, was the severe injury suffered by one of our congregation, Randel Rowley, who was foreman of masonry construction. He was blown from a high scaffold by the gusty winds, and hospitalized for 80 days, legs in cast for 1 ½ years. “The problems in building this church started with the foundations. It was found that most of our footings were on good, solid limestone, except the northeast corner of the Fellowship Hall, which was on soft clay. It became necessary to drive steel piling to provide the needed bearing, and in some areas, 50-foot pilings were required. … “A need to economize on construction became evident when bids on the structure exceeded both the architect’s estimate and the church building budget. One of the first economy moves was to raise the elevation of all floors … by four feet, thereby saving a large volume of excavation and reducing the height of the retaining wall behind Fellowship Hall. A secondary benefit of this change was the elimination of steps down to the rear entrance, thus providing better access from the parking lot. …”

225th Tidbits: Open the Doors

There’s a children’s ditty – with hand gestures - that goes: Here is the church Here is the steeple Open the doors to see all the people. From the outside, St. Paul’s may be the big building on the hill, but it is the people inside who really “make” St. Paul’s. Over the past 225 years, thousands of people have come through those doors, each making some impact, small or large. Here are some of the impacts that people have today:

Hands are raised:

•To decorate bulletin boards or the sanctuary for holidays, or to change the hymn numbers in the sanctuary.

•Holding puppets as part of the Luther League puppet ministry, enhancing APPS and worship, sharing joy at local nursing homes and assisted living facilities.

•To carry the cross and light the candles during worship.

Voices are raised:

•In intercessory prayer, praying for others in their need.

•In song in the choir in its service leadership and anthems, and in the congregation, joining in worship.

•On Sundays to read lessons, lead prayers, and preach.

•In study, sharing and conversation as we Live Our Faith Together (LOFT).

Hands reach out:

•To shut ins through the Shepherd’s Ministry, keeping them within the St. Paul’s circle.

•To distribute personal and cleaning supplies to community members as part of Bountiful Blessings.

•To share St. Paul’s doings in the media and in social media.

•To collect the offering, greet everyone before and after the service, and to prepare the altar and elements before and after worship.

•To share the Body and Blood.

Doors open:

•To welcome eight local congregations for a joint ecumenical Vacation Bible School every June.

•To various community groups, including weekly aerobics, Girl Scouts and the Mountainside Baroque early music ensemble for rehearsals, a summer music academy and performances.

•For Beginnings Montessori School. Hands on instruments:

•Make music for worship, weddings and funerals, and just to fill our beautiful sanctuary with beautiful sound.

•Operate a sound system and a slide show to make worship more accessible.

•Keep our building clean, our grounds groomed and our pavements clear.

•Drive a van to provide transportation. Hands craft:

•Food for APPS, funeral luncheons, Loaves & Fishes, and potluck dinners. They make cookies for shut-ins and meals for Bountiful Blessings.

•Prayer shawls and cancer bags.

•Renovations and repairs.

•The bread for communion. Hands, voices and minds lead:

•Through church council and its committees – Education/Faith Formation, Evangelism, Finance, Ministry in Daily Life, Property, Social Ministry (Fellowship), Stewardship, Worship and Music, and Youth – to direct, manage, decide.

•Young people during the Children’s Taking Faith Home message, during Children’s Church and during APPS.

•As they prepare deposits and financial reports.

•In contemplation as they consider candidates to call for the next pastor.

Feet carry us:

•As we walk to raise money to fight cancer and hunger.

•As we walk together in faith

Proudly powered by Weebly